Katrín Jakobsdóttir

Katrín Jakobsdóttir (born 1 February 1976) is an Icelandic politician serving as the 28th and current prime minister of Iceland since 2017. She has been a member of the Althing for the Reykjavík North constituency since 2007. She became deputy chairperson of the Left-Green Movement in 2003 and has been their chairperson since 2013. Katrín was Iceland's minister of education, science and culture and of Nordic co-operation from 2 February 2009 to 23 May 2013. She is Iceland's second female prime minister, after Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir. On 19 February 2020, she was named Chair of the Council of Women World Leaders

Education

Katrín was born in Reykjavík. She graduated from the University of Iceland in 1999 with a bachelor's degree with a major in Icelandic and a minor in French. She received her M.A. in Icelandic literature from the same university in 2004 for a thesis on the work of popular Icelandic crime writer Arnaldur Indriðason.

Non-political career

She worked part-time as a language adviser at the news agency at public broadcaster RÚV from 1999 to 2003. She then freelanced for broadcast media and wrote for a variety of print media from 2004 to 2006 as well as being an instructor in lifelong learning and leisure at the Mímir School from 2004 to 2007. She did editorial work for the publishing company Edda and magazine JPV from 2005 to 2006 and was a lecturer at the University of Iceland, Reykjavík University and Menntaskólinn í Reykjavík from 2006 to 2007.

Political career

She became deputy chairperson of the Left-Green Movement in 2003 and has been their chairperson since 2013. She has been a member of the Althing for the Reykjavík North constituency since 2007.[1] Katrín was Iceland's minister of education, science and culture and of Nordic co-operation from 2 February 2009 to 23 May 2013.

Prime Minister (2017–present)

Before becoming Prime Minister, she was chairperson of the Left-Green Movement.[4] In the wake of the 2017 Icelandic parliamentary election, President Guðni Th. Jóhannesson tasked Katrín with forming a governing coalition to consist of the Left-Green Movement, the Progressive Party, the Social Democratic Alliance, and the Pirate Party.Coalition talks between the four parties formally began on 3 November 2017, but were unsuccessful because of Progressive Party concerns that her coalition would have too thin a majority.] As a result, she sought to lead a three-party coalition with the Independence Party and Progressive Party. After coalition talks were completed, President Guðni formally granted Katrín a mandate to lead the government, which was installed on 30 November. She is the second woman to serve as Prime Minister of Iceland. According to political scientists, her government "combines conventional economic and social emphases (e.g. support for the regions and primary industries) with opposition to European integration." Despite being a coalition government of the left socialist Left-Greens, the centre (Progressive Party) and the right wing (Independence Party), the coalition was stable throughout 2018.

Political positions[edit]

Katrín opposes Icelandic membership of NATO, but as part of the compromise between the Left-Greens and their coalition partners, the government does not intend to withdraw from NATO or hold a referendum on NATO membership. She opposes Iceland joining the European Union. The coalition government does not intend to hold a referendum on continuing Iceland's accession negotiations with the EU.

Personal life

Katrín is married to Gunnar Sigvaldason and the mother of three sons (born 2005, 2007 and 2011). She hails from a family which has produced many prominent people in Icelandic politics, academia and literature. She is the younger sister of twin brothers Ármann Jakobsson and Sverrir Jakobsson, who are both professors in the humanities at the University of Iceland. Katrín is the great-granddaughter of the politician and judge Skúli Thoroddsen and the poet Theodóra Thoroddsen, and granddaughter of the engineer and MP Sigurður S. Thoroddsen. The poet Dagur Sigurðarson is her maternal uncle.

5 Fast Facts About Katrín Jakobsdóttir, Iceland’s New Prime Minister

In November 2017, Katrín Jakobsdóttir became the new prime minister of Iceland as part of the country's Left-Green Movement. In addition to being only the second woman to ever hold the position, the 41-year-old is a staunch environmentalist who is hoping to make the country carbon neutral by 2040. Here are some facts about Iceland’s new PM. 1. SHE’S AN EXPERT IN CRIME FICTION. Before entering politics, Jakobsdóttir attended the University of Iceland, where she received her bachelor’s degree in Icelandic while minoring in French in 1999. She got her masters in Icelandic literature at the same school, where she wrote her dissertation on Arnaldur Indriðason, a popular crime author in Iceland. 2. SHE IS ICELAND’S FORMER EDUCATION MINISTER. After the 2008 financial crisis led to Iceland’s first left-leaning government taking power, Jakobsdóttir served as the country’s Minister of Education, Science and Culture. She continues to tout the importance of those subjects by promising to put more money from the country’s current economic upswing into health and education. 3. SHE IS ICELAND'S FOURTH PRIME MINISTER IN TWO YEARS. Jakobsdóttir’s tenure as prime minister begins as the country’s political system deals with a series of scandals from the past few years, including fallout from government officials being named in the Panama Papers. This has led to constant shuffling of the prime minister position, and Jakobsdóttir, as part of the Left-Green party, will be the fourth since 2016. The previous prime minister, Bjarni Benediktsson, saw his coalition collapse in 2017 after a scandal occurred involving his father, which prompted a snap election in October. Though a coalition with the Progressive Party and Benediktsson’s Independence Party led to Jakobsdóttir becoming PM, she must still work with Benediktsson, who is now the country’s Minister for Finance and Economic Affairs. The three ruling parties will all have a hand in different aspects of the government, but the situation between them could be tenuous, as no partnership of this nature has lasted a full term in the country. 4. A POLL NAMED HER THE “MOST TRUSTED ICELANDIC POLITICIAN” AHEAD OF THE COUNTRY’S PRESIDENT In 2016, an Icelandic market research poll named Jakobsdóttir the country’s most trusted politician, with 59.2 percent of people saying they trusted her. This was ahead of then-president Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson at 54.5 percent. Other polls suggest that most of Jakobsdóttir’s support comes from voters aged 18 to 29, with many of them being women. 5. OH, AND SHE WAS IN A MUSIC VIDEO Before Jakobsdóttir entered politics, she popped up in the music video for "Listen Baby” by the Icelandic pop rock band Bang Gang. What’s her role in the video? Well, she runs. A lot. “Two friends of mine asked me to play that role, and it's mainly doing the running bits,” Jakobsdóttir told USA Today. She understands, though, the importance of trying her hand in many different areas of Icelandic culture, telling the site, “So, we all have to play a lot of different parts, not least [of all] in a small society like Iceland."

How to build a paradise for women. A lesson from Iceland

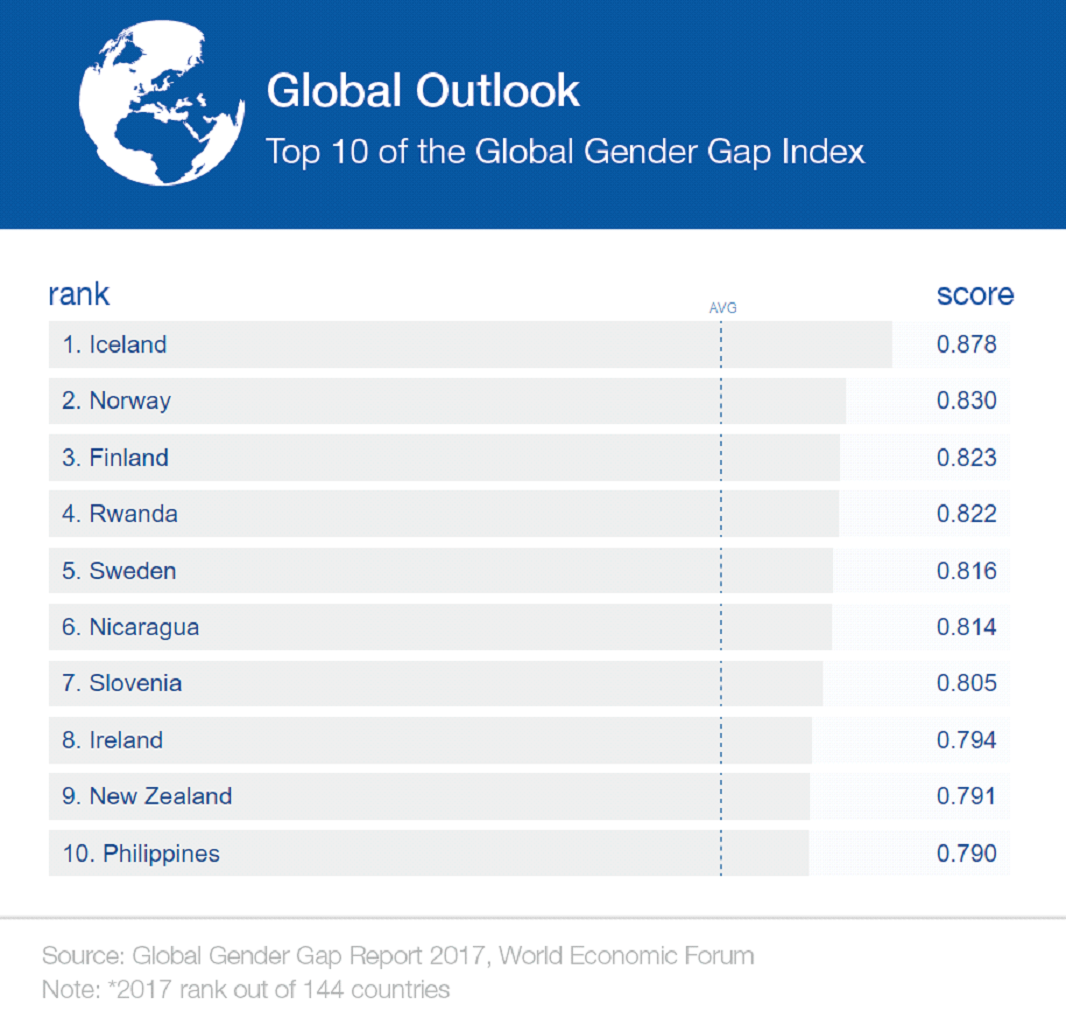

Iceland is honoured to be a frontrunner in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, and as Prime Minister I am frequently asked about Iceland’s progress, and how we got to where we are. However, I am rarely asked where we should head from here and what we could do better. It should be noted that the Nordic countries occupied four out of five of the index’s top places in 2017. This is not a coincidence. Nordic countries are all welfare states and support for universal social policies is generally high, and such policies are the key ingredient in building societies that work for women.

Women’s solidarity and social change

The women’s movement has been effective and organised across the Nordic countries. In Iceland, women have repeatedly shown extraordinary solidarity through the women’s day off, which in 1975 attracted 90% of women in Iceland who refused to perform work that day. This highlighted all the visible and invisible tasks, paid and unpaid, that women undertake every day, everywhere, and form the foundation of our communities. This day was the beginning of a huge and powerful movement that resulted in an enormous social change in Iceland. The solidarity that the Icelandic women’s movement built in the 1970s and the 1980s laid the foundation for welfare policies that have liberated women in the country in many ways. My generation was born into an atmosphere of women’s liberation. As children we were surrounded by role models, where women took up more space in society than they had ever done before. Women were marching on the street and the first female president, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, was elected. For us, it meant that we were not forced to choose between having a family or having a career; a choice that women in many countries are faced with, limiting women’s participation in the labour market and their access to decision making.

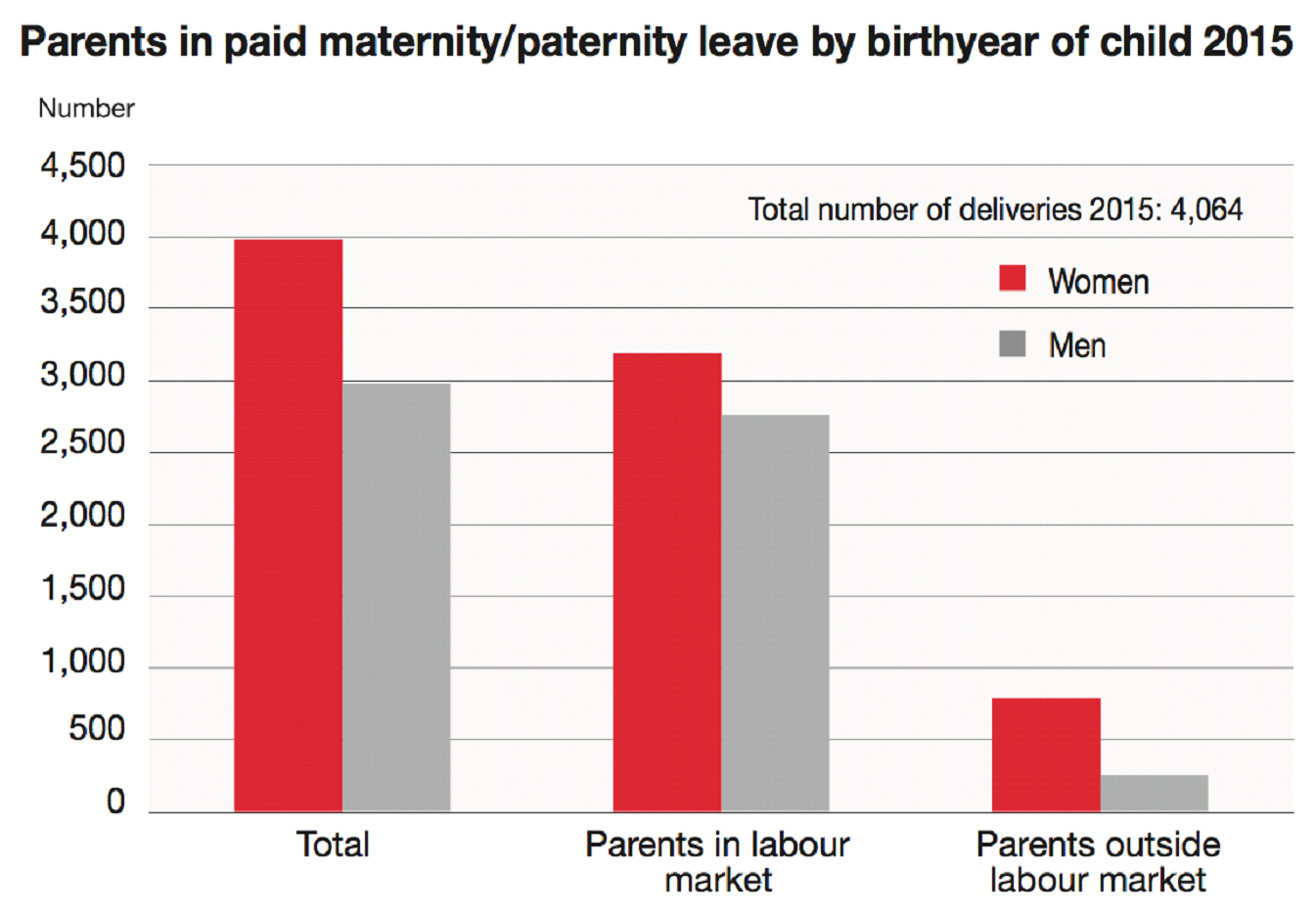

Childcare and parental leave

Two public policies are worth mentioning in this context. First, universal high-quality childcare transformed women’s opportunities to participate in the economy and in society at large. As women still carry the bulk of child rearing, childcare costs prevent women across the world from joining or re-joining the labour market and/or participating in politics. Second, well-funded shared parental leave – with a use-it-or-lose-it proportion for fathers – addresses the systematic discrimination women have suffered at work, due to the possibility alone that they might have children. If men are as likely to take a break from work to care for children, this structural discrimination diminishes. Many female politicians in Iceland would never have got where we are today if it wasn’t for childcare and parental leave. I am an excellent example of that. And in this sense, governments and parliaments can lead the way by adopting policies that have been shown to bridge the gender gap, rather than widen it.

No country has eliminated violence against women

Yet, despite Iceland’s progress, structural inequalities are still persistent in the country. Most recently the #metoo movement exposed systematic harassment, violence and everyday sexism that women at all levels of Icelandic society are subjected to. Moreover, the movement revealed the multiple discriminations suffered by migrant women in a country that has throughout history been relatively ethnically homogenous. It remains alarming that no country in the world has managed to find ways to eliminate violence against women. Violence against women is both a cause and a consequence of women’s inequality. To this day, the Gender Gap Index does not measure violence against women and neither does any other similar index. To be sure, violence is difficult to measure. Police reports only tell half the story and official and societal definitions of what counts as violence may differ between cultures. Yet, some kind of comparison on rates of violence against women would, without doubt, put further pressure on governments to step up their game to eliminate those persistent human rights violations.

A part of the solution: Women Leaders Global Forum

This year, and for the following three years, the Government and Parliament of Iceland will serve as co-hosts to the Women Leaders Global Forum (WLGF), along with Women Political Leaders (WPL). This unique forum attracts women from politics, businesses, academia and civil society to share ideas and solutions that help build better societies and promote gender equality. It can serve as a platform to explore ways to further reduce gender-based inequalities across the world. Because while there is a significant difference in women’s position in various corners of the world, the nature of the discrimination women suffer is similar. There is still work to be done and we must not relent in the fight for women’s equality, even though we reach important milestones. The Gender Gap Index, the 2018 edition of which is launching next month, should serve as an encouragement for all of us to do better. By learning from one another and sharing experiences, I believe that we will move closer towards our goal. As Prime Minister of Iceland, I am deeply committed to building a world where women are free to reach their full potential, to the benefit of all.

This is why Iceland ranks first for gender equality

For Icelanders, it is a source of pride to be the frontrunner in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index for the ninth year in a row. Ranking at the top is a confirmation of the successes achieved in recent decades and inspires us to continue to work towards complete equality of status, influence and power of men and women. What is the secret to Iceland’s success? What are the lessons learned? In short, it is that gender equality does not come about of its own accord. It requires the collective action and solidarity of women human rights defenders, political will, and tools such as legislation, gender budgeting and quotas. Iceland, despite being an island, is not isolated from progress towards gender equality. As is the case worldwide, our incremental progress can firstly be attributed to the solidarity of women human rights defenders challenging and protesting the monopoly of power in the hands of men and the power of men over women. Secondly, the success can be attributed to women taking power and creating alternatives to the male dominant “truths” and making the invisible realities of women visible, most importantly discriminatory practices including sexual harassment and abuse. Lastly, Iceland’s progress can be attributed to women and men sharing power with each other as decision-makers and gradually having more men supporting the give and take of gender equality. As such, the Icelandic case is nothing exceptional. It has been influenced by cultural, political, religious, social, academic and economic currents that have washed ashore and been domestically cultivated and created. Culturally, there exists a notion of “strong women”. Despite being mythical, it has its roots in reality, as women enjoyed certain liberties and had cultural and religious authority during the commonwealth period that lingered on throughout the ages. On the religious front, diversity was embraced in the “pre-modern”, pagan society. There were gods and goddesses, as well as women and men serving as cultural and religious authorities. Women were priestesses and oracles, poets and rune masters, merchants and medicine doctors, enjoying respect in society. This religious diversity ended with the advent of Christianity in the year 1000 when the diverse group of Gods and Goddesses was replaced by one monolithic God. At the same time, women were no longer deemed "good enough" to publicly represent God, and despite relatively equal status, women did not have the right to vote or to be represented in Iceland’s parliament – the oldest in the world, established in 930. Women began to fight for the right to be good enough. They partly succeeded in 1914 and 1915 when women were granted the legal right to be Protestant priests, and the right to vote and run as political candidates, respectively. However, there was a huge gap between the progressive, rights-based law development and prevalent cultural norms and societal reality, which kept men in their place of power enjoying their “first-mover advantage” and continued to hold women back. This situation remained until a critical mass of educated women penetrated the fortresses surrounding the palaces of knowledge, the academia, and feminism became a mass movement in the 1960s and 1970s, uniting women in their struggle for equal rights and influencing politics.

During these decades, women began to take power to define and redefine the world we live in and even invent new “truths” from where they were standing. Feminism began to infiltrate theology with God referred to as She by the first woman ever to be inaugurated as a priest in Iceland in 1974, or 974 years after Iceland became Christian and 60 years after it became legal for women to serve as priests. Thirty-eight years after that, in 2012, Iceland’s first female bishop was inaugurated. It had taken a century. On the political front, women’s solidarity by means of political organising has been instrumental in promoting gender equality in Iceland. During the period from 1915 to 1983, only 2%-5% of members of Parliament were women. It is also important to note that the first Icelandic women elected to a municipal government in 1908 and to parliament in 1922 were represented by women’s lists, not the traditional political parties. When this political experiment was repeated several decades later with the establishment of the Women’s Alliance in 1982, it led to major changes and a jump in women’s participation in politics. The political platform of the Women’s Alliance consisted of “women’s demands”, such as childcare for children to enable women to participate in the labour market on an equal footing with men, which were supported by female constituents. Subsequently, in 1983, for the first time in Icelandic history, there was a sharp increase in the number of women in parliament jumping from five to 15 MPs of a total of 60 in a single election. An Icelandic political scientist, Dr Auður Styrkársdóttir, has compared the waves of women’s democratic enfranchisements with natural upheavals, such as earthquakes or volcanoes. Unlike the steady rise in women’s representation in the other Nordic countries, male dominance in Iceland was only broken by women’s collective action and solidarity. The Women’s Alliance ceased to exist in 1999 after working relentlessly from inside parliament, influencing the political debate and the political agendas of the traditional political parties. Gradually, “women’s issues” were brought into the political agendas of other parties and women in these parties began to serve a more meaningful role than previously, when they were the icing on the cake, a decorative flower within male-dominated political parties and the lists of candidates.

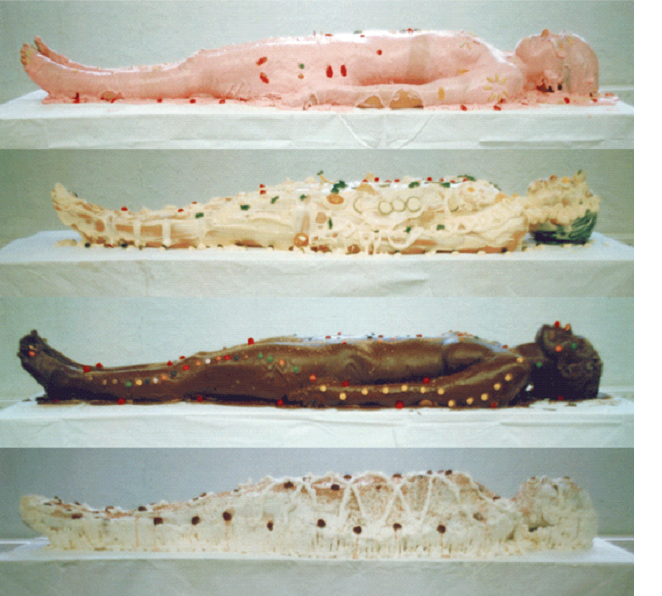

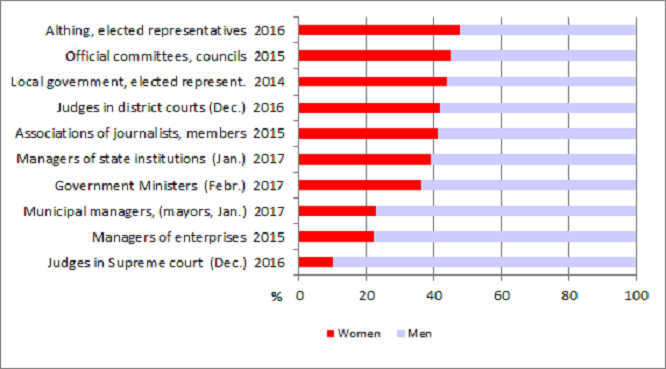

Women Good Enough to Eat, 1997 Image: The Icelandic Love Corporation During the century that has passed since women got national suffrage, there has been a rise in the number of women running as candidates for elections. Equal sex ratio is still not enough if the aim is to reach gender equality in political representation. To reach that aim, women have to be placed high(er) on the list of candidates to have an equal chance to be elected into power. One of the success stories in Iceland is that among the long-established political parties, only one party does not apply some kind of gender quota rules, such as a “zipper system” when selecting men and women on its lists of candidates. In 2016, women accounted for 48% of elected representatives in parliament (since recent elections it has dropped to 38%). It is also a great achievement in this long struggle that the number of women in the cabinet has, in recent years, begun to reflect the share of women in parliament. The executive power has been referred to as the highest glass ceiling. After more than 100 years, there is almost political equality.

In conclusion, the status of women in Iceland was, historically, relatively equal to men even though legal equality was not ensured until 1976. Still, every woman is rendered vulnerable if she does not have or is stripped of real power by a system that does not de jure or de facto protect women’s rights vis-a-vis men in case of conflict. This applies in particular to situations of violence against women and girls perpetrated by family members or strangers within or outside their homes. The life of a woman in a system that does not protect her human rights and security is like a Russian roulette: women are at the mercy of “their masters” – good or bad men – because the system protects the interests of (potential) perpetrators of violence. In such a system, some women are lucky while others draw or are handed the short straw. Consequently, historically and still today, the struggle of women human rights defenders is not about good or bad men per se. Instead, it is all about use and abuse of power and authority, namely converting a system where a culture of impunity prevails over a culture of accountability for violence against women (and men). The struggle is aimed at changing the system – the normative and the legal rules governing our lives – which has been shaped by people with and in power. This is also the reason why women need to have equal power and to be in power. Simple as that. The systemic political and economic empowerment of women went hand in hand with the “invasion” of feminist scholars into the cradle of knowledge in the 1960s and 1970s, resulting in the emergence of a new reality that was previously unspoken and unseen. The term “sexual harassment” is a case in point. It was introduced in the 1960s, deriving its meaning from the experience of the so-far powerless and voiceless victims, the survivors, who were given a loudspeaker with this new feminist terminology. Legislation prohibiting sexual harassment was introduced in Iceland as well as other predominantly western countries at the time. But the pervasive culture of male power and privilege meant that sexual predators continued to be protected despite the legal prohibition, by men and women alike, who were implicated in their crimes by either taking part by silencing the victims or by naming, blaming and shaming them. Just before the allegations against Harvey Weinstein in the United States came to light, the Government of Iceland had collapsed after convicted sex offenders had their "civil standing" restored under legislation from the 19th century using the terminology “restoration of honour”. Information regarding the cases, originally withheld and later released, constituted a breach of trust in the minds of one of the smaller coalition partners, resulting in the dissolution of the government. In September, the respective clause in the law was repealed. In general, it is impressive to see how social media is creating a wave of protest where women are speaking out, repeating #metoo and telling the world that they have had enough. This is happening in Iceland as it is elsewhere. The “business as usual” element of the “honour restoration cases” mobilised the survivors, their parents, feminists and the general public into a loud protest represented by the hashtag #höfumhátt, which means "Let's not be silenced". What are the remaining challenges? In Iceland, as in the other Nordic countries, the welfare state is supportive of gender equality by granting parental leave to both parents resulting in not only more power sharing but also an increase in sharing of the responsibility for running a home and family. Ideas about masculinity are changing among young people which will most likely contribute to the elimination of gender segregation in the labour market in near future.

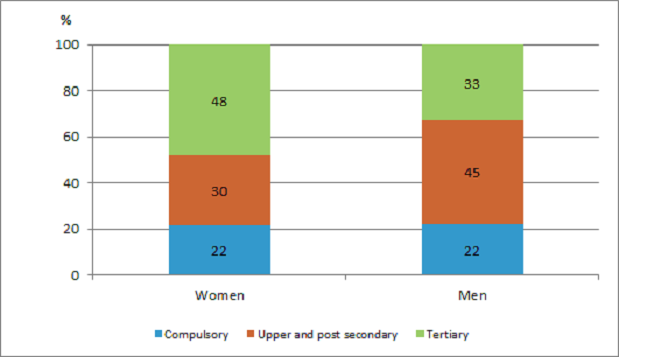

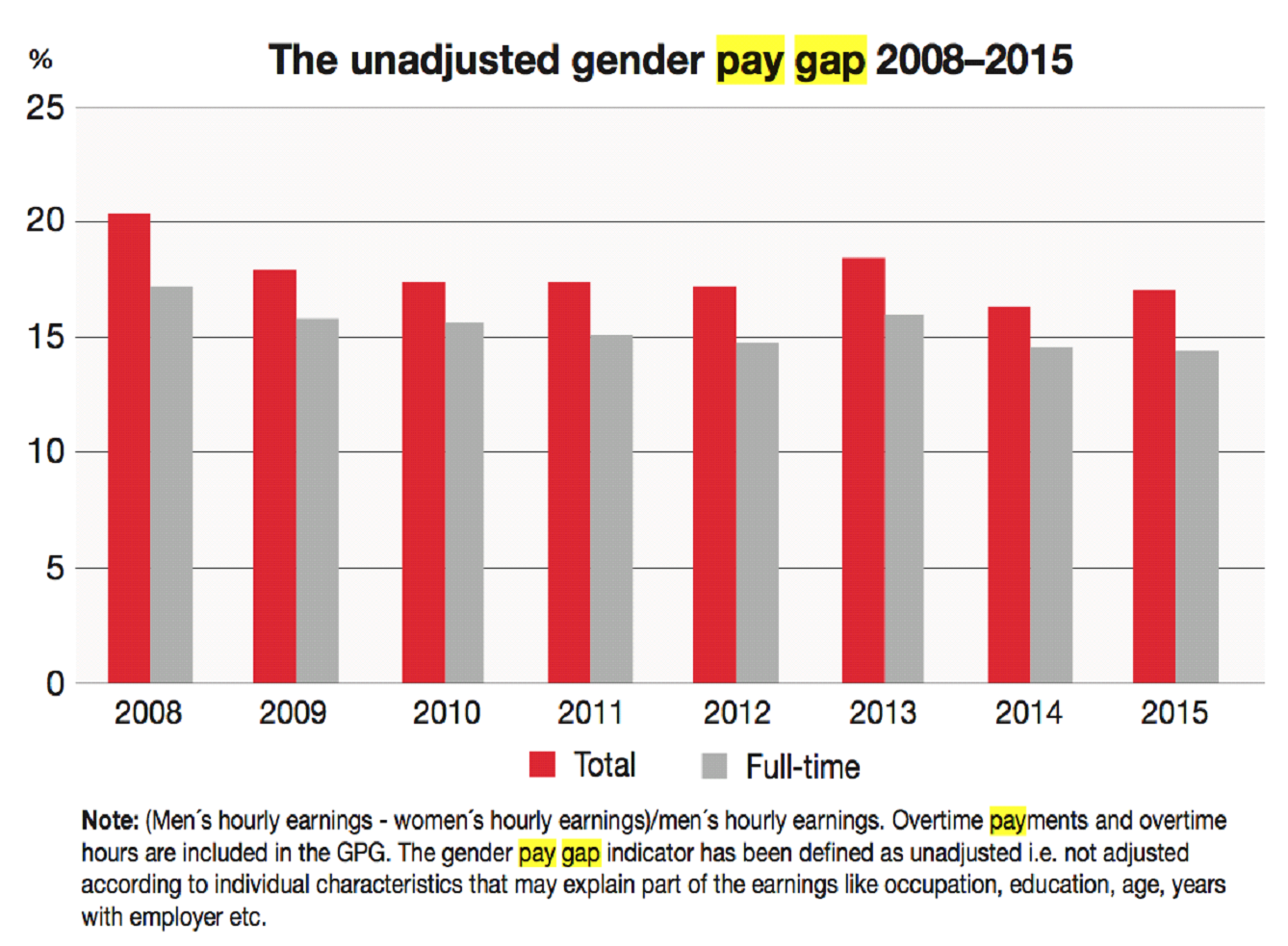

Still, there are challenges that remain to be resolved, not least the gendered reality we live in where so many things are assumed about individuals or groups on the basis of their sex, sexual orientation or identity. Such gendered assumptions and notions continue to cause problems such as how occupations predominantly held by women, such as nursing, are valued less than men’s occupations, such as construction. There is a gender pay gap for work of equal value despite the existence of a law on equal pay since 1961. Icelandic women have been protesting against this imbalance by going on general strike since 1975. Image: Statistics Iceland Now, more than 40 years later, equal rights are supported by political will, as evident in the introduction of the law on equal pay certification. This legislation is based on a tool called the Equal Pay Standard, which aims to eliminate the adjusted gender pay gap. The standard will apply to all companies and institutions with 25 full-time staff positions. Implementing the standard will empower and enable employers to truly implement a management system of equal pay according to the principle of equal pay for equal work and work of equal value. They will thereby comply with the act on the equal status of men and women and fulfil the demands of international treaties, such as the International Labour Organization Conventions, the Beijing Platform of Action and the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). The intention of the government to implement the Equal Pay Standard through legislation was widely debated in Iceland, just as every other legislative measure on the matter has been. In turn it has brought the gender equality debate into mainstream politics and policy-making, away from the margins where it often resides. It is believed that the Equal Pay Standard will be instrumental in eliminating the gender pay gap. What’s the secret? Walk the walk, don’t just talk the talk.

Now, more than 40 years later, equal rights are supported by political will, as evident in the introduction of the law on equal pay certification. This legislation is based on a tool called the Equal Pay Standard, which aims to eliminate the adjusted gender pay gap. The standard will apply to all companies and institutions with 25 full-time staff positions. Implementing the standard will empower and enable employers to truly implement a management system of equal pay according to the principle of equal pay for equal work and work of equal value. They will thereby comply with the act on the equal status of men and women and fulfil the demands of international treaties, such as the International Labour Organization Conventions, the Beijing Platform of Action and the Convention to Eliminate All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). The intention of the government to implement the Equal Pay Standard through legislation was widely debated in Iceland, just as every other legislative measure on the matter has been. In turn it has brought the gender equality debate into mainstream politics and policy-making, away from the margins where it often resides. It is believed that the Equal Pay Standard will be instrumental in eliminating the gender pay gap. What’s the secret? Walk the walk, don’t just talk the talk.

Outstanding Achievements

Iceland's new leader: 'People don't trust our politicians'

Katrín Jakobsdóttir says her goal is to restore confidence as she becomes Iceland’s fourth prime minister in two years

By the age of eight, Katrín Jakobsdóttir was reading Agatha Christie. A couple of decades later, she wrote her masters dissertation on the works of Arnaldur Indridason, a king of Nordic noir. In literature, crime is her thing. It is a specialism that might stand her in good stead in her new real-life job, as prime minister of Iceland and, at 42, Europe’s youngest female leader. “Crime fiction,” she said, only half-joking, “is about not really trusting anyone. And that’s generally how politics works.” Brought almost to its knees by the 2008 crisis, Iceland has since been rocked by a succession of ethical and financial scandals that have left voters deeply disaffected by what many see as the endemic – and largely unpunished – cronyism and corruption of their political and business classes. As a consequence, Katrín, a slight, driven 42-year-old is the country’s fourth prime minister in two years. A socialist, a feminist and an environmentalist, she heads the Left-Green Movement and has bold policy goals on climate change, gender equality and public services. But perhaps her most daunting challenge will be to change this north Atlantic island’s political culture, and to restore the confidence of its 340,000 people in their politicians – while heading an unlikely coalition with the two conservative parties most closely associated with those scandals. “A lot has happened in Icelandic politics, and people really don’t trust Icelandic politicians,” Katrín said in an interview in her central Reykjavik office. “I can’t blame them. But now we need to think how we can best rebuild trust in politics.” She said many on the left were still “very angry with me” for her decision to form a left-right coalition after last October’s parliamentary elections – Iceland’s fifth since 2017 – with the conservative Independence party, part of nearly every Icelandic government since 1944, and the centre-right Progressives. The leader of the former, Bjarni Benediktsson, has been embroiled in multiple scandals: Iceland’s last government, which he led, collapsed less than a year after taking office when it emerged he had known for months that his father wrote a letter supporting the rehabilitation of a notorious convicted paedophile. After revelations in the Guardian, Bjarni also faced awkward questions over the sell-off, when he was still an MP, of millions of króna of his assets in a big Icelandic bank’s investment fund just as the government was seizing control of the country’s failing financial sector at the height of the crisis. His name also appeared in the Panama Papers leak that forced the resignation of his predecessor as prime minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson. Then the leader of the Progressive party, Sigmundur Davíð stepped down in 2016 amid public fury at revelations that his family had sheltered money offshore.

People demonstrate against Sigmundur Davíð in Reykjavik. Photograph: Reuters A writer and academic with three young boys whose mother was a psychologist and whose twin brothers are both university professors, friends whisper that Katrín – known in Iceland, like everyone else, by her first name – has both Bjarni, her finance minister, and current Progressive party leader Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson, her transport minister, “round her little finger”. She, unsurprisingly, refuses to say very much about that, beyond “I know them well” and “everything is going very smoothly”. But scandal-tainted or not, going into government with a pair of alpha-male conservative heavyweights was absolutely the right thing to do, she said. First, the financial scandals date to a time, before the crisis, when there were “few ethical rules for politicians, no rules or regulations on how you present your interests,” she noted. “That was astonishing, but it’s no longer the case.” Beyond that, though, “I look at it pragmatically, not moralistically. I think, ‘We’re here now, we need to change the system, so we need everyone at the table.’ Not, ‘I’m not going to work with you because you did things I think are morally wrong.’” Codes of ethical conduct “don’t work like normal legislation”, Katrín insisted. “They work because everyone sits down together and says, ‘We need to work rules out for ourselves.’ And then they need to look carefully at how well those rules have worked, which we’re now doing.” A late developer economically and politically, Iceland needs “systemic change to restore confidence”, she said. “But doing it this way, having very different parties – in both their political perspective and their cultures – working together … Yes, it’s a gamble. But I really think it’s an opportunity for us to rethink, reinvent ourselves.” Proof of whether it pays off will be in the achievements of her government, which has a wafer-thin majority of just 35 MPs in the 63-seat Alþingi. Of Iceland’s four most recent governments, only one, the left-leaning administration in which Katrín served as education minister from 2009, served a full four-year term. It certainly has ambitions, the first of which is to boost spending on health, education and public transport after years of post-crisis austerity. Iceland fell into a deep recession following the 2008 crash, during which its three major banks failed with liabilities of 11 times the country’s GDP. The stock market plummeted by 97%, the value of the króna halved, and Iceland became the first western European country in 25 years to ask the IMF for a bailout. With a reformed financial sector, growth of 4.9% last year, and unemployment down at just 2.5%, the economy has bounced back strongly on the back of an unprecedented tourist boom, but that progress “has not been shared enough, or delivered into public infrastructure”, Katrín said. On the environment, Iceland aims to be carbon neutral by 2040 – a more ambitious target than the Paris climate accords. “It’s doable,” Katrín said confidently. “Iceland has renewable energy resources; we have a head start. But again, we won’t manage it unless everyone pulls together.” She is also determined to push the country further on gender equality. This month it became the first country in the world to enforce an equal pay standard, but Iceland “is not a gender paradise”, she said. “We have done a lot of good things here, but there are fewer women in this parliament than in the last one. We’re not there yet.” The #MeToo revolution was “as much of an eye-opener here as anywhere”, Katrín said, revealing a country in which entrenched inequality and male power games had survived untouched. Combating gender-based violence and discrimination would be “an absolute priority” starting at home, with government institutions and the political parties. But she is, she said, cautiously optimistic for the left. “I think the politics of this century are going to revolve a lot around left and right,” she said. “It’s about people who can hardly live on their salaries, people’s rights ... How people are treated. We’ve never had a greater need for equality. How we do it doesn’t matter.”

Gender equality: 'Battle for fundamental human rights'

Iceland is often held up as the poster child of gender equality, but as Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdottir told DW ahead of the 2018 Women Leaders Global Forum, even her country has to keep fighting.

DW: Iceland is often referred to as "the most gender-egalitarian country in the world." Would you agree? Katrin Jakobsdottir: I have often said that while we are proud of our place at the top of the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap list, women in Iceland are also very aware that even we — in this top global position of the "gender paradise" as Iceland is sometimes called — have work to do. While there is a difference in degree between women's equality in Iceland and some other corners of the world, the nature of the discrimination is the same. The gender pay gap still exists in Iceland, women still don't have equal power in Iceland's corporate and financial world, and we also have the serious problem of gender-based violence and sexual violence and harassment in Iceland, as most recently revealed by the #MeToo movement. Do you think your country's gender equality achievements are sufficient? No. The fight for gender equality won't be "over" or "sufficient" until we have eliminated gender-based discrimination in Iceland and across the world. Even though we reach a milestone here and there, we must never think that because of those milestones or goals reached, the fight for gender equality is something that we can allow ourselves to put on the backburner. I don't see the struggle for women's rights as a box-ticking exercise, this is a battle for fundamental human rights and it demands a shift in our cultures; we need to change how we treat and perceive each other. This is not a job of one generation, but many. And I want to look back and say that I played my part and that my government was a force for progress, not regression.

Katrin Jakobsdóttir is prime minister of Iceland, and a mother of three Icelandic women were active participants in the #MeToo movement, with thousands sharing their experiences of sexual harassment and assault on social media. These stories showed that cultural change is still missing in many areas of society. Would you agree? Yes. The #MeToo movement exposed systematic harassment, violence and everyday sexism that women in all layers of Icelandic society are subjected to. A recent study covering over 24,000 Icelandic women indicates that one in four women have experienced rape or attempted rape. An open dialogue on violence against women is likely to lead to more women speaking out about their experiences. So, if this is the story in the "most gender equal place" in the world, we can imagine what is going on across the world. I believe this is one of the most pressing human rights issues of our times. And to end violence against women we must end inequality between women and men so that all genders can flourish. The #MeToo movement pushed the topic of sexual harassment and the experiences of many women to the top of the list of issues where people are demanding change — not just in Iceland, but in many other countries. How can it have a positive and lasting effect? One of the things the #MeToo revolution has taught us all is that oppression of women thrives in silence. If we do not speak up and let it be known that we no longer tolerate certain behavior, things won't change. If we stay silent, women will keep on suffering. The #MeToo revolution has been a huge eye-opener and hopefully we will see the change needed. Read more: Margaret Ekpo, pioneering feminism in Nigeria As part of our presidency in the Nordic Council of Ministers next year, we will host an international conference on the impact of the #MeToo movement in September 2019. The conference will ask questions such as: Why did #MeToo happen now and why has the impact been so different between countries? What does the backlash against #MeToo tell us about present day sexual politics? I hope this conference will attract thinkers, activists and policy-makers from across the world so that we can seize the energy of #MeToo to bring about lasting positive social change.

Different countries have reacted to #MeToo in different ways, a conference in Iceland next year will look at why There is now gender quota legislation in Iceland to ensure women are fairly represented on company boards, and your administration is implementing a pay equity law. It was passed to ensure that by 2022, men and women in public institutions and private companies over a certain size will receive comparable salaries for comparable work. Why is it taking so long for the goal of equal pay to be achieved? It is interesting that while we have endless studies demonstrating that diversity on boards and in management is not only the right thing to do, but also best for business, the corporate world still persists. Despite the gender quota legislation, men still dominate on corporate boards and in the highest layers of management in Iceland's largest companies. Read more: Land of fire, ice and gender equality There is still this stubborn gender pay gap of about 4.5 percent in Iceland — and we're talking about the adjusted pay gap, that is pay for equivalent work. Our most recent tool to tackle the gender pay gap is the equal pay standard, which requires companies to prove they're paying women and men equally. This is already leading to changes in pay structures as companies, organizations and institutions have discovered that they were underpaying women. But I am also interested in the unadjusted and the overall pay gap between women and men, because that tells us the story of how our societies are made up and what kind of work we value and what kind of work we don't value. Looking at Europe, it's obvious that women are still widely under-represented in politics as well as business. What can women do to help shift the balance of power? We should look at this from the perspective of both men and women: What can we do as a society, what can we do together? Under-representation is not just a women's issue. Let's ask ourselves. What can men do? Well, they can start by acknowledging that we have not reached gender equality and take part in the change that is needed to eliminate inequality by bringing more women to the table. The Women Leaders Global Forum, hosted in Iceland this year and the following three years, is an important platform to find ways to take the next steps. Read more: In German politics, women still have a long way to go Then we constantly need to address the links between women's representation and women's inequality in other areas. Violence against women is a barrier to women's public participation, and online harassment can serve as a tool to push women out of the public space.

Four women who are 'part of the change' Women's economic independence is also a key factor to ensuring women's representation. And as women still carry the bulk of domestic and child rearing responsibilities, family policies are essential for women's participation in business and politics. I have said that I would not be where I am if it wasn't for shared parental leave (with a use-it-or-lose-it proportion for fathers) and universal childcare. If any policy-makers are wondering what to do to liberate women, my response is childcare and parental leave. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has often been described as one of the most influential politicians in the world. Do you think Mrs. Merkel has changed the way female politicians are perceived? I think Chancellor Merkel is one of the most influential politicians of our times and she will be remembered as such. While role models are important, I believe women's status is best improved through movements. I don't think any one woman in a certain position brings about change. But we are all a part of the change and I hope we continue moving in the right direction. Katrin Jakobsdottir has been prime minister of Iceland since 2017.