Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya

Sviatlana Heorhiyeuna Tsikhanouskaya or Svetlana Georgiyevna Tikhanovskaya (née Pilipchuk) (born 11 September 1982) is a Belarusian human rights activist and politician who ran for the 2020 Belarusian presidential election as the main opposition candidate. She is married to activist Sergei Tikhanovsky, who was a candidate for the same election until his arrest on 29 May 2020; she subsequently announced her intention to run in his place. The incumbent Alexander Lukashenko was officially declared the victor in a contest marred by allegations of widespread electoral fraud. Subsequently, Tsikhanouskaya claimed to have received between 60 and 70% of the vote and has appealed to Western countries to recognise her as the winner, although they instead called for a re-run and no longer recognise Lukashenko as President. Before running for president, Tsikhanouskaya was an English teacher and interpreter. She spent many summers in Roscrea, Co. Tipperary, Ireland, as part of a programme for children affected by the Chernobyl disaster. She is married to YouTuber, blogger, and activist Sergei Tikhanovsky, who was arrested in May 2020. The couple have a son and a daughter.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is the leader of Belarusian democratic forces

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is the leader of Belarusian democratic forces who beat the autocratic president Aliaksandr Lukashenka in a presidential election on August 9th, 2020, according to independent observers. She stepped into the race after her husband was arrested for his presidential aspirations. Lukashenka publically dismissed her as a “housewife,” сlaiming that a woman can't become president. Tsikhanouskaya united Belarusian democratic forces together with two other leaders – Maria Kalesnikava and Veranika Tsapkala. After her forced exile, Tsikhanouskaya inspired unprecedented peaceful protests around Belarus, some of which numbered hundreds of thousands of people. She visited more than 20 countries gathering support for free Belarus. She advocates for the release of 500+ political prisoners and peaceful changes through a free and fair election. In her meetings with Chancellor Merkel, President Macron, President von der Leyen, President Charles Michel, and other world leaders, she emphasized the need for a braver response to the actions of the Belarusian dictatorship. Tsikhanouskaya became a symbol of peaceful struggle for democracy and female leadership. Among dozens of other distinctions, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is a recipient of the Sakharov Prize awarded by the European Parliament. In 2020, Lithuanian President Nauseda and Norwegian MPs nominated her for the Nobel Peace Prize. She is included in Bloomberg's TOP-50 Most Influential People, Financial Times' Top 12 Most Influential Women, and POLITICO's Top 28 Most Influential Europeans.

Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya: How she took on an authoritarian leader despite her fears

n just a few months the opposition figure went from unknown stay-at-home mom to the leader of democratic Belarus. She told DW she's proud of both roles, and says that for millions of women, "the inner strength awoke." Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya was a political unknown just one year ago. Today, she has become the leader of the biggest protest movement in Belarus since the country gained independence. The wave of action she led has been awarded the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought by the European Parliament, and she has now been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize as well. "I can do everything. I can do it. I already proved it to the whole world. I'm not afraid. You think I can't take a leadership position? " she said in a DW interview ahead of International Womens' Day, which is observed annually on March 8.

Tsikhanouskaya holds a picture of activist Nina Baginskaya during the EU Parliament's 2020 Sakharov Prize ceremony

'I was a housewife ... What should I be ashamed of?'

Tsikhanouskaya emerged in 2020 as the face of the opposition to longtime authoritarian leader Alexander Lukashenko, and subsequently as the self-styled "leader of democratic Belarus." In May, when her husband Sergei Tsikhanousky, a well-known blogger and democracy activist, was barred from challenging Lukashenko for the presidency and arrested, she ran instead. The strongman president, who had been in office since 1994, did not take her seriously as an opponent and claimed publicly that "a woman can't be a president." He attempted to demean her experience as a stay-at-home parent: "She just cooked a tasty cutlet, maybe fed the children, and the cutlet smelled nice." But Tsikhanouskaya's determination to hit back at institutionalized misogyny struck a chord with millions of women in Belarus and abroad. Asked about Lukashenko's insults, she spoke of how he mocked "that I'm a housewife, I belong in the kitchen. He was trying to make fun of me," she said in a DW interview. But Tsikhanouskaya refused to even acknowledge the premise of his derision. "I was never offended by that because it is what it is. I was in fact a housewife for a number of reasons. That's true. Yes. If he wanted to insult me, he didn't succeed. It's the truth. What should I be ashamed of?" It may be beyond Lukashenko's imagination that a woman could rule the country. But the opposition leader has no doubt that her country disagrees with his sexist rhetoric about a woman taking over the office of president. "Yes, I'm more than convinced that it's possible. Because my allies and I, and all Belarusian women who took to the streets have proven their resilience, their strong character. So Belarusians won't have any doubts that a woman can become the future president of Belarus." 2020 marked a turning point in many ways for the former Soviet republic — and especially for Belarusian women. Lukashenko's security forces initially spared women, but that changed once they became the driving force during democratic protests. Images and reports emerged of women — from teenagers to grandmothers — being arrested, beaten and even tortured. Several prominent women activists were detained and driven into exile. Tsikhanouskaya said it was "an impulse of the heart" that propelled millions of Belarusian women to protest the electoral fraud. "Going out against violence — it was like an instinct. When we saw how many we were, we started being proud of ourselves. 'Here I am, I did it.' The inner strength awoke."

Police across Belarus have made mass arrests at pro-democracy marches; reports of violence and torture have emerged

'The fear was always there'

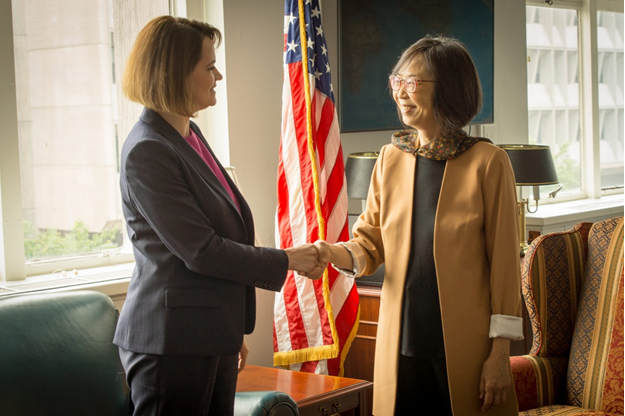

Tsikhanouskaya described her remarkable ascent to leadership as that of having no choice. "The fear was always there: that you end up in prison, what would happen to your children then? Every morning you live with a feeling of fear. It doesn't mean that I have overcome my fear. It means that you do something in spite of your fear, because there is no other way." Tsikhanouskaya and her children were put under immense pressure and were forced to flee the country. She has been living in exile in Lithuania since the election, from where she keeps on fighting for democracy. The European Union and the United States have not recognized Lukashenko's claim that he won the election. Meanwhile, Tsikhanouskaya has become her country's representative on the international stage. Several world leaders have met with her — among them German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Tsikhanouskaya met with Merkel in Berlin in October and described the longtime leader as "extremely friendly" during the conversation. "It was obvious that she has a sense of empathy, that she understands our pain, that she would really like to help us."

The opposition leader said that the 30-minute meeting focused on how Germany could help broker a possible dialogue between demonstrators and Belarusian authorities. "She's so straightforward," Tsikhanouskaya said of the longtime chancellor. Merkel shows "absolutely no arrogance and there's a sense of warmth coming from her. That doesn't contradict the notion of the strong woman she is known to be ... And it doesn't take tough talk to understand that she is a strong leader." Yet like the German leader, who has famously said she does not view herself as a feminist, Tsikhanouskaya said the term does not particularly apply to her, either. She emphasized her recent actions as instead being out of circumstance and necessity after her husband's arrest: "I wouldn't consider myself a feminist," she told DW.

What does the future hold for Belarus?

Will Tsikhanouskaya continue her own quest for the presidency? At the beginning of March, Belarusian authorities put her on a wanted list for allegedly "preparing for unrest." She told DW that "she is ready to be with the Belarusians for as long as they need me" but that she will not necessarily pursue the job herself. "If circumstances change and we'll have new elections — that's our goal — I don't plan to run again. But we don't know what the situation will be. It could be that ... the people will decide that, yes, we trust her again. I always say: 'If you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans.'"

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya: from 'Chernobyl child' in Ireland to political limelight

Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the woman who has been catapulted into political stardom in Belarus by her push to dislodge the man often referred to as Europe’s last dictator, may be an accidental challenger, standing in Sunday’s presidential election only because her opposition activist husband Sergei was arrested. But a hint of the strength and resilience that has made her a courageous if unlikely opponent who has refused to accept Alexander Lukashenko’s claim to victory in a poll marred by vote-rigging may have been present at age of 12, when she arrived to spend a summer in rural Ireland. Tikhanovskaya was one of the “Chernobyl children”, whose health was either directly or indirectly affected by the radioactive fallout of the 1986 nuclear disaster in neighbouring Ukraine and whom Irish families hosted for respite and recuperation.

Advertisement

Henry Deane, 72, and his wife Marian first accommodated Tikhanovskaya, who they knew as Svyeta, at their home in Roscrea, County Tipperary in the mid-1990s. “Two children arrived that year. Svyeta was a similar age to my daughter Mary, and she fitted right in,” Deane told the Guardian. “As a kid she was clearly intelligent, she had more knowledge of English than the others. She set herself up as a kind of interpreter and spokesperson for the others.” Deane said, however, that he could not have imagined the trajectory that life has taken for “this little girl”, as Lukashenko calls Tikhanovskaya disparagingly. “Some of the children were still clearly traumatised by the whole thing, the situation in those villages of Belarus at that time, not just because of Chernobyl, but the economy also, things were very difficult,” he said. Deane travelled to Mikashevichi, Tikhanovskaya’s home village, after he co-founded a Chernobyl charity. Mikashevichi was 30 miles (40km) north of the border with Ukraine and had been severely hit by the disaster. “Belarus’s hospitals were filled with children at the time who had all kinds of problems. Svetlana’s teacher was our interpreter. We travelled to Belarus regularly, visited the school and that’s how we met her and brought her over,” Deane said. In Roscrea, which has a population of 7,000, the children were given medical attention – eye and hearing problems were common. They were also taken on picnics, outings to the cinema in Tullamore and shopping trips. “They loved going to the cheapest stores such as Penneys [the name used by Primark in Ireland]. They were quite shocked by the size of people’s houses. “Within days you would see these children transformed before your eyes, good food and lots of it helped. Because food was not plentiful for them. They loved bananas and beans, our kids were amused by that.”

Tikhanovskaya looking after other Chernobyl children on a visit to Birr Castle, County Offaly, in Ireland in 1997 or 1998. Photograph: henry deane Most of the children who stayed with the Deanes came for a summer, perhaps two, but Tikhanovskaya came back again and again as she grew close to the family and the local community. For a couple of summers she even got a job helping out at a local Roscrea factory to earn money, Deane said. “She worked on the factory floor, the most menial tasks, but she was very glad to do it. She needed money for her studies in Brest [in western Belarus]. She was very humble and modest.” She returned to Roscrea each year, in her early 20s acting as an interpreter for children on the Chernobyl scheme. Was there any hint of early political idealism around the breakfast table in Roscrea? “Children at that time would not speak openly about the political situation in Belarus,” Deane said. “There was a fear of anyone getting to know their families were critical of the government. But Svyeta was open and talked about unrest. People were disenfranchised and they knew the voting was rigged.” He is astonished though to see her cast as a Joan of Arc figure, and says she has no long-term political ambition but has put herself forward out of concern for the people of Belarus. “Her first child was profoundly deaf, and she gave up work to help him. She moved the family to Minsk so that he could have the implant operation he needed. She poured her life into looking after her son and daughter. She is a devoted mother. She just wanted to be voted in so she could release political prisoners, which is noble of her, and please God it works.” Deane said that apart from “the odd encouraging text”, he had not spoken to her in recent weeks. “She was a lovely girl. My children and grandchildren all have very good memories of Svyeta … She was just a nice, genuine, sincere, and honest kid.”

They might not win, but 3 women are 'giving hope' to Belarus with an unlikely presidential bid

"I am not in politics for power. I am in it for justice," said Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya who is running against Belarusian president Alexander Lukaschenko Often referred to as "Europe's last dictator," Alexander Lukashenko is normally crowned the victor in an event that has had the same outcome over his 26 years of iron-fisted rule. But this time, it's different. Three women are standing against Lukashenko, one of the world's most authoritarian leaders, in a challenge that symbolizes the electorate's hunger for change. Just a few weeks ago, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Veronika Tsepkalo and Maria Kolesnikova had no plans to take on the president. Now, they hold rallies with tens of thousands of their supporters — the largest expression of dissent Belarus has seen in years — asking them to vote Lukashenko out. "What the three women have been able to do is unite a lot of their supporters, and you can see by the number of people they are attracting with their political rallies that there is strong support for the kind of change that they are professing," said Emily Ferris of the Royal United Services Institute, a London think tank. Although there is little doubt that Lukashenko, 65, will hold on to power after the election Sunday, the trio have created "unprecedented activation of Belarusian society," said Alesia Rudnik, a research fellow at the Center for New Ideas, a Minsk-based think tank. "Despite the election result, these three figures managed to embody the fight against the regime by raising awareness and giving hope to ordinary Belarusians," she said. Tsikhanouskaya, 37, a former teacher and translator with no political experience, registered as a presidential candidate after the electoral commission denied the registration of her husband, the popular political blogger Syarhei Tsikhanouski. He was later detained at a rally in his wife's support and remains jailed on multiple charges, according to the country's investigative committee. He has dismissed the charges as a provocation. Veronika Tsepkalo's husband, Valeriy, a former ambassador to Washington, was denied registration as a presidential candidate and fled to Russia last month after he was tipped off that his arrest was imminent. The two women joined forces with Kolesnikova, the campaign manager for Viktor Babariko, a former banker and opposition candidate, who was arrested on charges that his team has called "absurd" and later disqualified from the race by the electoral commission. Since they unified their campaigns last month, the three women have become the faces of opposition in Belarus. An image of them with three different symbolic gestures — a clenched fist for Tsikhanouskaya, a victory sign for Tsepkalo and a heart shape for Kolesnikova — has gone viral. Maria Kolesnikova, right, Svetlana Tsikhanouskaya, candidate for the presidential elections, and Veronika Tsepkalo, gesture during a news conference in Minsk, Belarus, in July. Although Tsikhanouskaya is the only one actually running for office, she insists that she is no politician. She said she registered as a presidential candidate last month to support her husband, who was snubbed by the electoral commission. Since then, she has transformed from a self-described "mother and wife" indifferent to politics into an outspoken opposition leader who has challenged Lukashenko to a face-to-face live TV debate. "I am not in politics for power. I am in it for justice," she declared in an address on state TV last month. "We have two options — to continue living in poverty and empty promises or build a Belarus that we deserve."

Outstanding Achievements

Weekly achievements roundup of the Sviatlana Tskihanouskaya’s Office – February 21-28

The creation of a center-based on BYPOL, a plan of help to Belarus, and calls with doctors, resistance leaders in residential areas, and volunteers. Results of the work of the Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya for the week of February 21-28 – At the initiative of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, BYPOL served as a base for creating a Situation Analysis Center. The Situation Analysis Center’s tasks are to strengthen Belarusian activists’ security, monitor street activity, and neutralize the potential threats. – Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s representative for economic reforms Ales Aliakhnovich spoke about the Plan of macroeconomic assistance that the EU promises to Belarus after the departure of Lukashenka. A visa-free regime for Belarusians and new investments were on the agenda. – We are preparing to launch a website platform where everyone can safely take the initiative and take action within the framework of the Victory Strategy of Belarusians. – Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya called the resistance leaders in Belarus’s residential areas to share and listen to the plans on peaceful street protests and agree to coordinate their actions. – Tsikhanouskaya held online meetings with the representatives of the Medical Solidarity Fund and doctors. During her working visit to Switzerland (March 7-10), Sviatlana expects to meet with the WHO and the Red Cross representatives to tell them about the repressions against the medical community in Belarus. “No one is going to step back – everyone is determined and optimistic,” the health workers said. – Leader of democratic Belarus held a call with the volunteers to answer their questions and thank them for their selfless work. At the call, they discussed what makes the volunteers carry on fighting. Most of them said that the main reasons are faith in people and disagreement with the regime’s violence. – Tsikhanouskaya’s Office held repeated consultations with the representatives of the Norwegian company Yara on the topic of their cooperation with Belaruskali. Belaruskali is notorious for carrying on with the repressions against workers. – Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya spoke to foreign media on the situation in Belarus: Bild (Germany), Zeit (Germany), Al Jazeera, Gazeta Wyborcza (Poland). She also spoke with the Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon and Belarusian publications – Stolin.by and “Brestskaya Gazeta”. – Franak Viacorka answered the most popular questions using the Office chatbot @AskOffice_Bot. Among them are questions about vaccines, protests, and the rehabilitation of political prisoners. – The head of the Cabinet of representatives Valery Kavaleuski and the representative for economic reforms Ales Aliakhnovich addressed the British lawmakers, informed them about the current situation in Belarus, and called for continuing efforts to put pressure on the regime and support political prisoners in Belarus. The possible visit of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya to the UK was also discussed. – Ms. Tsikhanouskaya spoke at a discussion organized by the Lithuanian mission to the OSCE and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee. They discussed the launch of an international investigation into the crimes of the Lukashenka regime. – Mr. Kavaleuski took part in a briefing on Belarus organized by the deputy of the House of Representatives of the Congress Marcy Kaptur with the support of the Coalition of Central and Eastern Europe in the United States. As a result, they discussed the measures that the United States can take to increase the pressure on the regime, such as economic sanctions, support for the repressed and the civil society of Belarus, and the issues of energy security in our country. They also discussed the prospects and preparations for Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya's visit to the United States. – Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya held a conversation with the Belarusian Culture Solidarity Foundation on the campaign to exclude NGTRK from the European Broadcasting Union. – The international team of Tsikhanovskaya's office held online and offline meetings with diplomats and representatives of the governments of Germany, Poland, Finland, Portugal, as well as the European Commission. They discussed vaccines for Belarusians, an international investigation of human rights violations in Belarus and a tribunal, assistance to civil society, and sanctions against the regime.

Struggle for a democratic Belarus enters second year Twelve months since Belarusians first shocked the world with an unprecedented wave of protests against dictator Alyaksandr Lukashenka, the biggest political crisis to rock the East European nation since the collapse of the USSR is still far from resolved. In late summer 2020, I spent three weeks in Minsk reporting on the popular movement that sprang up in the wake of Belarus’s deeply flawed August 9 presidential election. Lukashenka almost certainly lost the vote to challenger Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya but declared himself the winner by a landslide margin, sparking nationwide demonstrations calling for change. It was a heady moment full of optimism, energy, courage, and remarkable levels of civility. Even amid the heightened emotions and sense of history that characterized those early weeks of protest, it was soon obvious that the Belarusian revolution was destined to be an overwhelmingly peaceful and courtly affair, at least on the part of the protesters. In an August 22, 2020, column entitled, “The Belarus revolution may be too velvet to succeed,” I posed the question of whether this approach would prove effective against the ruthless police state apparatus assembled by Lukashenka. “The protesters are generally very sweet, polite, and peaceful. Many are young, middle class Belarusians who work in the country’s booming IT industry and come to rallies dressed in form-fitting hipster ensembles,” I reported from Minsk. “Unlike events in Kyiv in 2013-14, there is no militant edge to the demonstrations. Indeed, this revolution is so velvet that at times it feels positively sleepy.” One year on, those observations remain pertinent. The peaceful protest movement has long since been forced off the streets and its leaders have been exiled abroad, while Belarusian society has been subjected to a brutal crackdown on a scale unprecedented in modern European history. Nevertheless, opposition to Lukashenka continues, and the Belarus dictator is widely seen both at home and abroad as illegitimate. The ability of Belarus’s opposition forces to keep the protest movement alive for an entire year is a remarkable achievement in itself. Most revolutions either succeed or are snuffed out within a period of around three months. That has not proven the case in the struggle for a democratic Belarus. The country’s pro-democracy movement has refused to succumb to the terror tactics of the regime, which have seen tens of thousands detained and hundreds of political prisoners sentenced to extended prison terms amid widespread reports of torture and other human rights abuses. The public have fought back with ever more inventive demonstrations of opposition including flash mob protests and impromptu patriotic singalongs. In an atmosphere of mounting repression, even wearing red socks has become an act of rebellion. With the hard line response of the security forces making protest actions inside Belarus physically risky, the focus has shifted online and to the activities of exiled Belarusian opposition groups. From her base in Lithuania, opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya has toured Western capitals, recently meeting with US President Joe Biden and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson as part of her tireless campaign to keep Belarus high on the international agenda. Exiled former security service officials have sought to chronicle the human rights abuses of the regime and encourage defections among their ex-colleagues. Meanwhile, a major recent data hack by a group calling itself Belarusian Cyberpartisans has exposed a tremendous amount of information about the Lukashenka regime and the activities of the security services. These efforts have not succeeded in forcing Lukashenka from power, but they have helped to maintain pressure on the regime and prevented the momentum of the protest movement from ebbing away entirely. Over the course of the past year, such grassroots activities have also created the bedrock of a future civil society that bodes well for the country’s long-term development.

Belarus opposition leader unveils memorial to Polish freedom

Belarusian opposition leader on Friday helped unveil a new monument commemorating Solidarity, the Polish trade union and freedom movement that played a historic role in the collapse of communism in eastern Europe. Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, the main opposition candidate to challenge longtime dictator Aleksander Lukashenko in an election last year, attended the unveiling alongside Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski. At a news conference ahead of the inauguration, she said the struggle for freedom in Poland has been an inspiration for her people. “The history of the Polish Solidarity movement is especially close and important for Belarus,” she said. “These events inspired Belarusians both when they took place back in Soviet times and later when a new dictatorship emerged in our country and Belarusians began to rely on the experience of our neighbors in fighting it.” The monument is made up of large letters reproducing Solidarity’s iconic logo. Friday is the 32nd anniversary of the first partially free elections in Poland after decades of communism, an achievement of Solidarity. Tsikhanouskaya met with Belarusians living in exile on Thursday, and was greeted by a crowd of Belarusians and Poles. Many Poles feel a strong sense of support for the struggle for freedom in Belarus, a fellow Slavic nation on their eastern border. On Friday she also met with Polish President Andrzej Duda. She expressed gratitude to the Polish people and the governments at all levels for supporting the Belarusian struggle against dictatorship